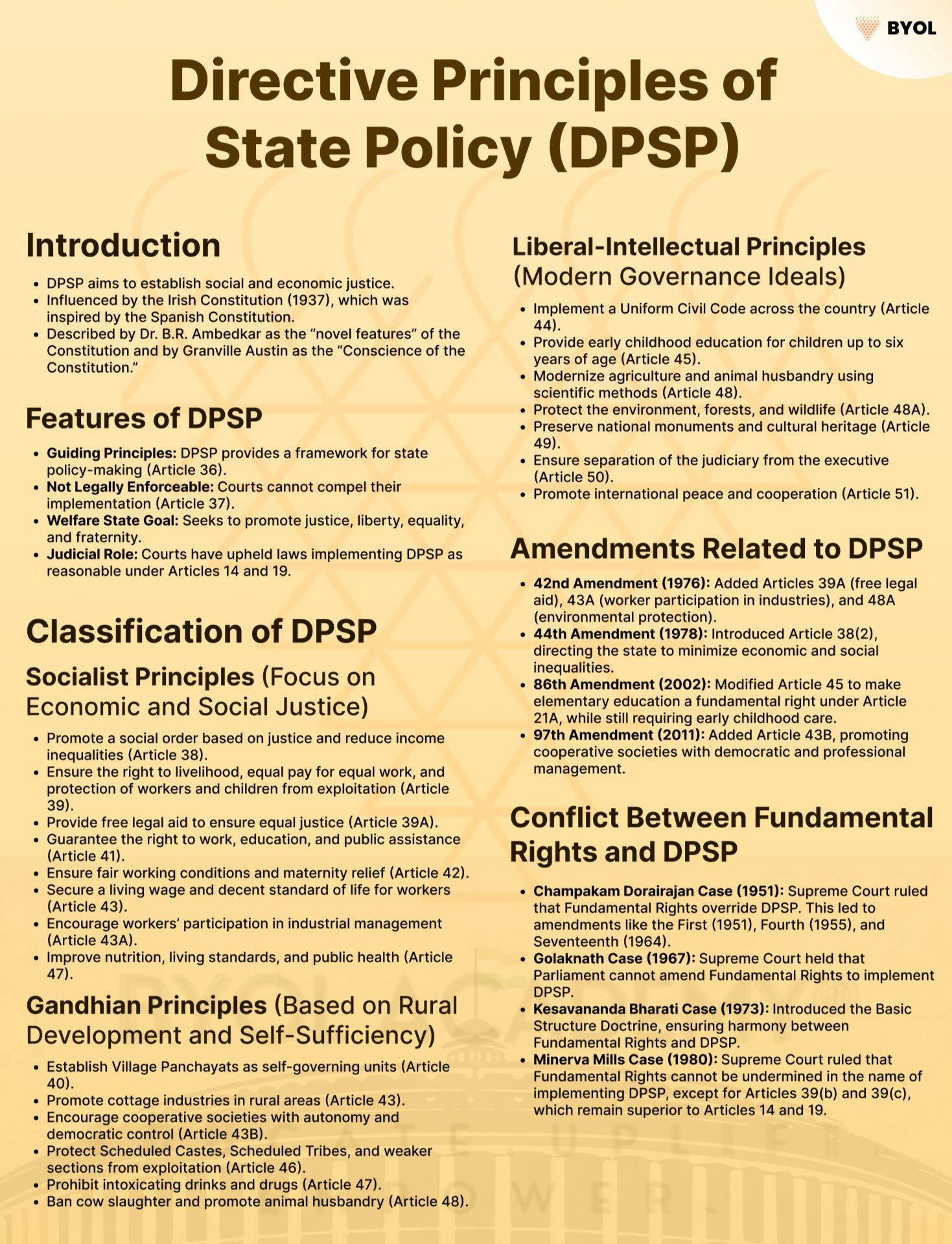

Introduction

The Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), in Part IV (Articles 36-51) of the Constitution, aim to establish social and economic justice. They were influenced by the Irish Constitution of 1937, which had its roots in the Spanish Constitution. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar called them “novel features” of the Constitution, while Granville Austin described them as the “Conscience of the Constitution”, emphasizing their role in governance and public welfare.

Features of the Directive Principles

- Guiding Principles – Directive Principles of State Policy are guidelines to the state in making laws, covering legislative, executive, and administrative matters (as defined in article 36).

- Inspired by the 1935 Act – They are similar to the Instrument of Instructions in the 1935 Government of India Act. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar noted that while both are mandates, the Directive Principles instruct the legislature and executive.

- Welfare State Goal – They have a vision of building a welfare state, which would ensure justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, unlike the police state of colonial rule.

- Not Legally Enforceable – As per Article 37, they are non-justiciable, meaning courts cannot enforce them. However, they remain fundamental to governance, and the State must apply them in law-making

- Judicial Role – Over time, the Supreme Court has upheld laws implementing Directive Principles by deeming them ‘reasonable’ under Article 14 (equality before law) and permissible restrictions under Article 19 (six freedoms), thereby safeguarding such laws from being struck down.”

Classification of the Directive Principles

The Constitution does not officially classify the Directive Principles, but they can be grouped into three categories: Socialistic, Gandhian, and Liberal-Intellectual.

Socialist Principles

These principles focus on social and economic justice, aiming to establish a welfare state. They direct the State to:

- Promote a social order based on justice and reduce inequalities in income and opportunities (Article 38).

- Ensure the right to livelihood, prevent wealth concentration, ensure equal pay for equal work, and protect workers and children from exploitation (Article 39).

- Provide free legal aid to ensure equal justice for the poor (Article 39A).

- Guarantee the right to work, education, and public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness, and disability (Article 41).

- Ensure fair working conditions and provide maternity relief (Article 42).

- Secure a living wage and decent standard of life for workers (Article 43).

- Encourage workers’ participation in industrial management (Article 43A).

- Improve nutrition, living standards, and public health (Article 47).

Gandhian Principles

These principles are based on Mahatma Gandhi’s vision for rural development, self-sufficiency, and social justice. They direct the State to:

- Establish Village Panchayats as units of self-government (Article 40).

- Promote Cottage Industries in rural areas (Article 43).

- Encourage Cooperative Societies with autonomy and democratic control (Article 43B).

- Protect SCs, STs, and weaker sections from social injustice and exploitation (Article 46).

- Prohibit intoxicating drinks and drugs harmful to health (Article 47).

- Ban cow slaughter and improve the breeds of milch and draught cattle (Article 48).

Liberal-Intellectual Principles

These principles reflect liberal and modern governance ideals. They direct the State to:

- Implement a Uniform Civil Code across the country (Article 44).

- Provide early childhood education for children up to six years of age (Article 45).

- Modernize agriculture and animal husbandry using scientific methods (Article 48).

- Protect the environment, forests, and wildlife (Article 48A).

- Preserve monuments and cultural heritage of national importance (Article 49).

- Ensure separation of the judiciary from the executive (Article 50).

- Promote international peace and cooperation (Article 51).

New Directive Principles

- The 42nd Amendment Act (1976) expanded the Directive Principles by adding the new provisions:

- Providing free legal aid to the poor (Article 39A).

- Encouraging worker participation in industry management (Article 43A).

- Protecting and improving the environment (Article 48A).

- The 44th Amendment Act (1978) introduced Article 38(2), directing the State to reduce economic and social inequalities.

- The 86th Amendment Act (2002) modified Article 45, making elementary education a fundamental right under Article 21A, while still requiring early childhood care for children below six years.

- The 97th Amendment Act (2011) added Article 43B, promoting cooperative societies with democratic and professional management.

Sanction Behind Directive Principles

Though not legally enforceable, Directive Principles guide the State in policymaking. Article 37 emphasizes that they are fundamental to governance.

Moral and Political Force

- B.N. Rau recommended classifying rights into justiciable (Fundamental Rights) and non-justiciable (Directive Principles).

- Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar argued that no government could ignore them.

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar believed that the people would hold governments accountable for neglecting them.

Why They Are Not Legally Enforceable

- Limited financial resources at the time of independence.

- Diverse socio-economic conditions made uniform implementation difficult.

- The new government needed flexibility to prioritize policies.

- The framers relied on public opinion rather than courts to ensure compliance.

Criticism of the Directive Principles

The Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), though fundamental in governance, have been criticized on several grounds:

- No Legal Force – DPSPs are non-justiciable, meaning they cannot be enforced by courts. Critics like “K.T. Shah” called them “pious superfluities,” while “Chaudhry Nasiruddin” contended that these principles are ‘no better than the new year’s resolutions, which are broken on the second of January’.

- Lack of Logical Arrangement – The principles lack systematic classification and mix major socio-economic issues with minor concerns. Scholars like N. Srinivasan and Ivor Jennings have pointed out the absence of a consistent philosophy.

- Outdated and Conservative – DPSPs are based on 19th-century British socialist ideals, which critics like Sir Ivor Jennings argue may be irrelevant in modern India.

- Potential Constitutional Conflicts – DPSPs can create tensions between the Centre and states, the President and Prime Minister, or Governors and Chief Ministers. K. Santhanam warned that the Centre could pressure states to implement them, leading to possible government dismissals.

Conflict Between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

Justiciability of Fundamental Rights and non-justiciability of Directive Principles have led to the problem from the start of the Constitution.

- Champakam Dorairajan Case (1951) – Fundamental Rights > Directive Principles. But the Supreme Court allowed Parliament to amend Fundamental Rights to implement Directives, leading to amendments like First (1951), Fourth (1955), and Seventeenth (1964).

- The Golaknath Case (1967) – Court ruled that Fundamental Rights cannot be abridged through constitutional amendments.

- Parliament’s Response – The 24th Amendment (1971) transferred the power to amend Fundamental Rights to Parliament. The 25th Amendment (1971) introduced Article 31C. This Article ensures that laws implementing Articles 39(b) & (c) (socialist principles) will not be struck down for violating Articles 14, 19, or 31.

- In the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973), the Supreme Court upheld the first provision of Article 31C but struck down the second, stating that judicial review is a basic feature of the Constitution and cannot be removed.

Distinction Between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles

| Fundamental Rights | Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) |

| Negative in nature – They prohibit the State from taking certain actions that violate individual rights. | Positive in nature – They direct the State to take actions for socio-economic development. |

| Justiciable – They are legally enforceable by the courts in case of violation. | Non-justiciable – They are not legally enforceable by courts if violated. |

| Aim to establish political democracy by ensuring individual freedoms and rights. | Aim to establish social and economic democracy by promoting equality and welfare. |

| Have legal sanctions, meaning their violation can lead to legal consequences. | Have moral and political sanctions but cannot be enforced in courts. |

| Protect individual rights, ensuring personal liberty and freedom. | Promote collective welfare, focusing on the interests of society as a whole. |

| Do not always require legislation for implementation; they are directly enforceable (e.g., Right to Equality). | Require legislation for implementation (e.g., Right to Education was initially a DPSP, later made a Fundamental Right). |

| The courts can strike down laws violating Fundamental Rights as unconstitutional. | The courts cannot invalidate laws violating DPSPs but may interpret laws in harmony with them. |

The 42nd Amendment Act (1976) expanded Article 31C, granting Directive Principles supremacy over Fundamental Rights (Articles 14, 19, 31), but the Minerva Mills case (1980) struck down this extension as unconstitutional, restoring the primacy of Fundamental Rights, except for Article 39(b) & (c), which remain superior to Articles 14 & 19. “The 44th Amendment Act (1978) abolished Article 31 (Right to Property), removing it as a Fundamental Right and relegating property rights to a legal right under Article 300A, thus reducing conflicts with Directive Principles.” The Supreme Court held that Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles must be balanced, like two wheels of a chariot, and Parliament can amend Fundamental Rights to implement Directive Principles, provided it does not violate the basic structure of the Constitution.

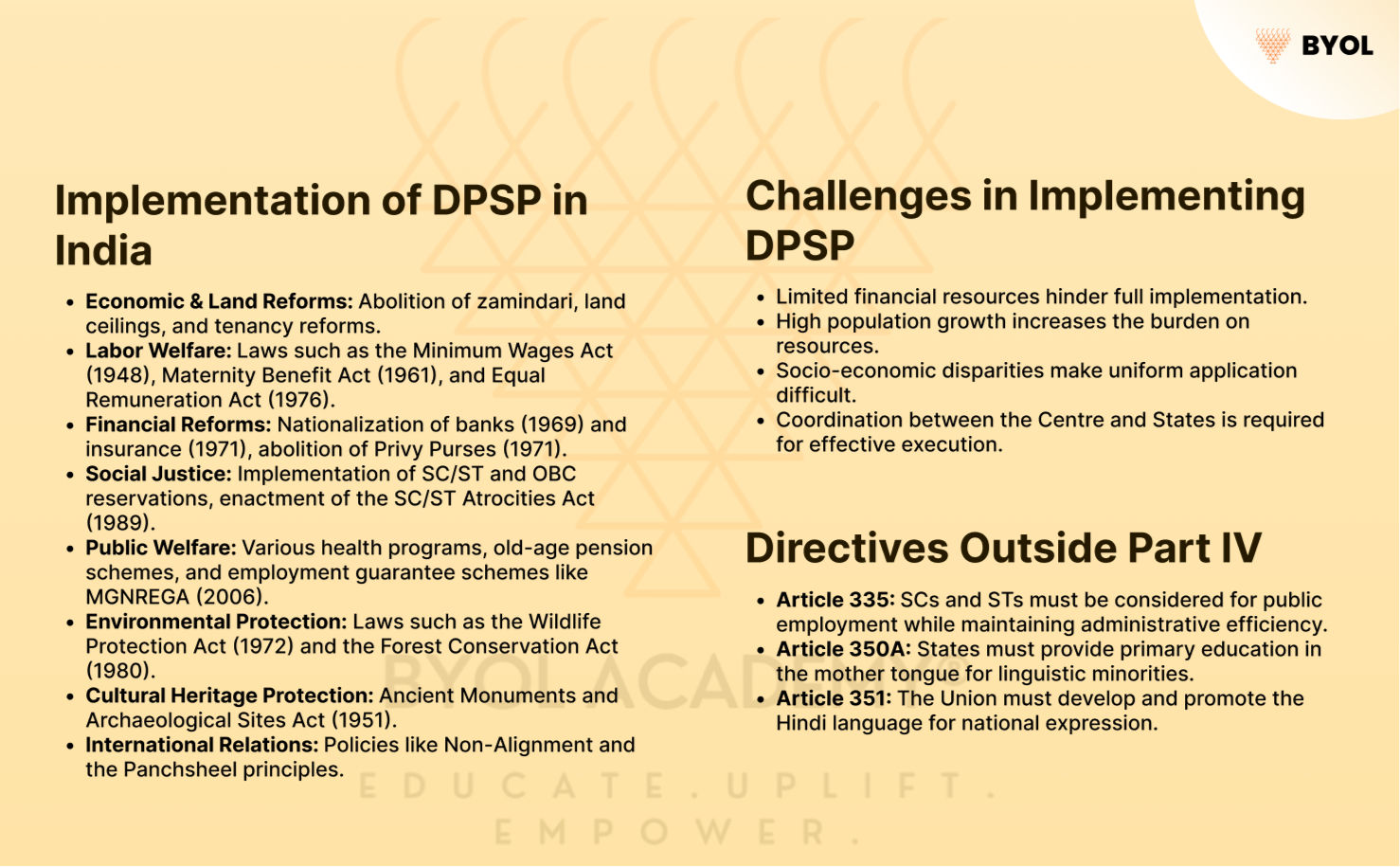

Implementation of Directive Principles

- Economic & Land Reforms: Planning Commission (1950) (replaced by NITI Aayog, 2015), Land Reforms – abolition of zamindari, land ceilings, tenancy reforms.

- Labor Welfare: Minimum Wages Act (1948), Child Labour Act (1986, amended 2016), Maternity Benefit Act (1961), Equal Remuneration Act (1976).

- Financial Reforms: Nationalisation of banks (1969), insurance (1971), abolition of Privy Purses (1971).

- Equal Justice: Legal Services Authorities Act (1987) (Lok Adalats), Separation of Judiciary-Executive (CrPC, 1973).

- Small-Scale & Rural Development: Khadi & Village Industries Boards, Integrated Rural Development Programme (1978), MGNREGA (2006).

- Environmental Protection: Wildlife Protection Act (1972), Forest Conservation Act (1980), Pollution Control Boards.

- Panchayati Raj & Social Justice: 73rd & 74th Amendments (1992), SC/ST & OBC Reservations, SC/ST Atrocities Act (1989), National Commissions for weaker sections.

- Public Welfare: Health programs for TB, AIDS, malaria, old-age pension schemes for people above 65 years.

- Cultural Heritage: Ancient Monuments Act (1951) for heritage protection.

- International Peace: Non-Alignment & Panchsheel policy.

Challenges

- Financial constraints

- Population pressure

- Centre-State issues

- Socio-economic disparities

Despite challenges, DPSPs continue to influence policy making in India.

Directives Outside Part IV

Apart from Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs) in Part IV, the Constitution includes other non-justiciable directives:

- SCs & STs in Services (Article 335, Part XVI) – Their claims in appointments must be considered while maintaining administrative efficiency.

- Mother Tongue in Education (Article 350-A, Part XVII) – States must ensure primary education facilities in the mother tongue for linguistic minorities.

- Promotion of Hindi (Article 351, Part XVII) – The Union must develop and spread Hindi as a means of national expression.

These directives, though non-enforceable in courts, are given due importance by the judiciary as part of constitutional interpretation.

Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP)

| Article No. | Subject Matter |

| 36 | Definition of State |

| 37 | Application of the principles in this part |

| 38 | State to secure a social order for the promotion of people’s welfare |

| 39 | Principles of policy to be followed by the State |

| 39A | Equal justice and free legal aid |

| 40 | Organisation of village panchayats |

| 41 | Right to work, education, and public assistance in certain cases |

| 42 | Just and humane working conditions & maternity relief |

| 43 | Living wage, etc., for workers |

| 43A | Workers’ participation in industrial management |

| 43B | Promotion of co-operative societies |

| 44 | Uniform Civil Code (UCC) for citizens |

| 45 | Early childhood care & education for children below six years |

| 46 | Promotion of educational & economic interests of SCs, STs & weaker sections |

| 47 | State’s duty to improve nutrition, standard of living & public health |

| 48 | Organisation of agriculture & animal husbandry |

| 48A | Protection & improvement of the environment, forests & wildlife |

| 49 | Protection of monuments & national heritage |

| 50 | Separation of judiciary from the executive |

| 51 | Promotion of international peace & security |